Our group mainly studies the problems associated with synthetic aperture radar (SAR) and explores the Earth, or even other planets, with it. SAR is one of the most important instruments for Earth observation. We are entering the golden age of SAR remote sensing. Unlike most optical instruments, SAR is an active sensor that transmits pulses toward the Earth and then receives the back-scattered echoes. Therefore, SAR does not require the illumination from the Sun and can image in daylight or at night. SAR operates at microwave bands in the electromagnetic spectrum. The microwave signals can go through clouds, which enables SAR to work in all-weather conditions.

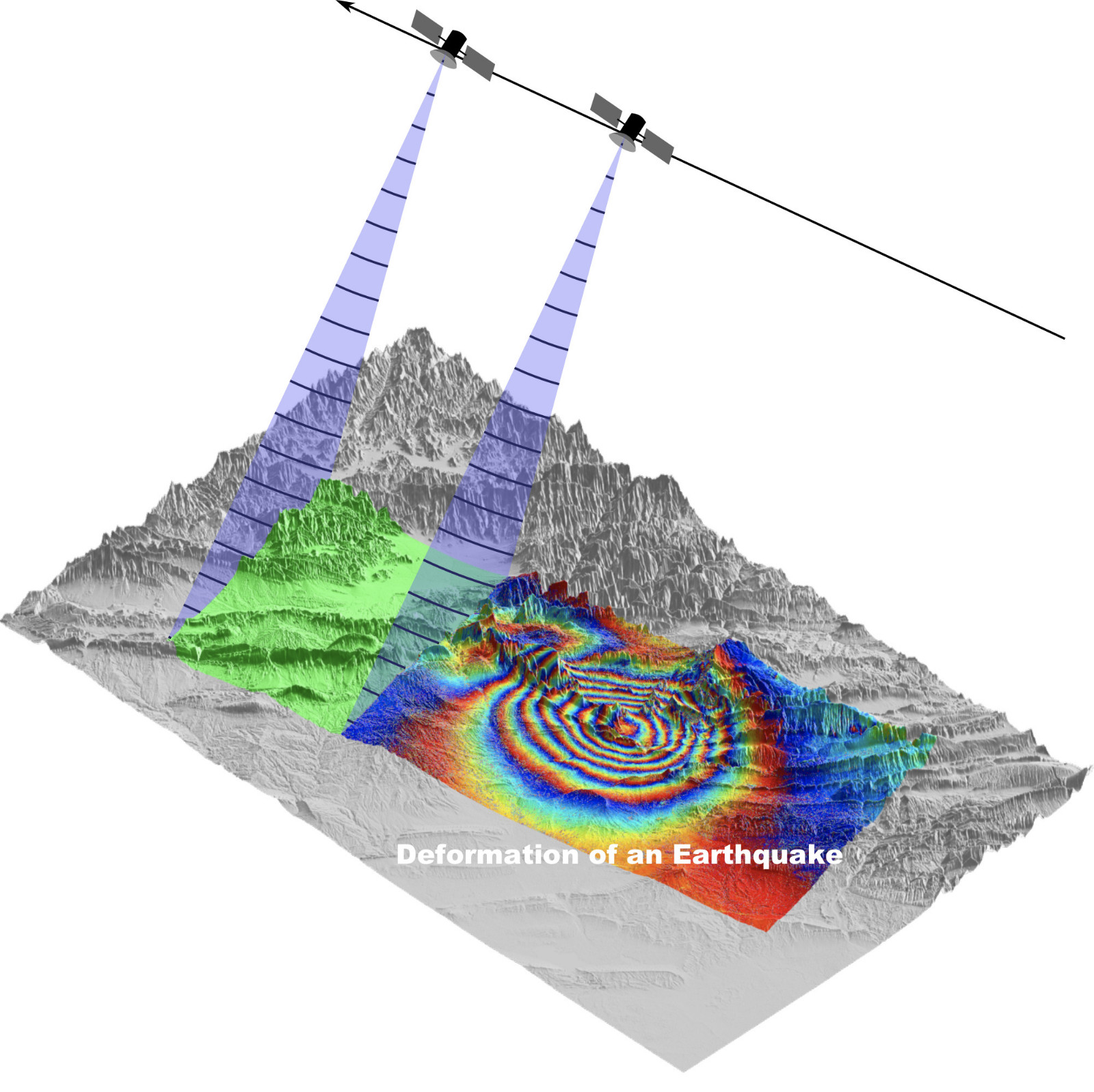

The development of synthetic aperture radar interferometry, or InSAR, in the last few decades further enables SAR to image the targets in the third dimension, acquiring either topography or deformation. InSAR measures deformations with a precision on the order of its own wavelength and thus achieves the amazing centimeter or even millimeter precision. Coincidentally, most of the deformations on the Earth’s surface are at the scale of radar wavelengths (Yes, there are deformations almost everywhere in the world. You just cannot see it in most cases, but InSAR can). Therefore, InSAR is widely used in engineering, earth science and hazard response. In particular, it is revolutionizing a wide range of Earth science fields. Driven by various applications with its unique capabilities, SAR and InSAR are spreading beyond academia and are being commercialized by a growing number of companies around the world. Analysts value the SAR market at roughly $4 billion, and expect that figure to nearly double over the next five years (Rosen, 2021, Science).

SAR Signal and Image Processing

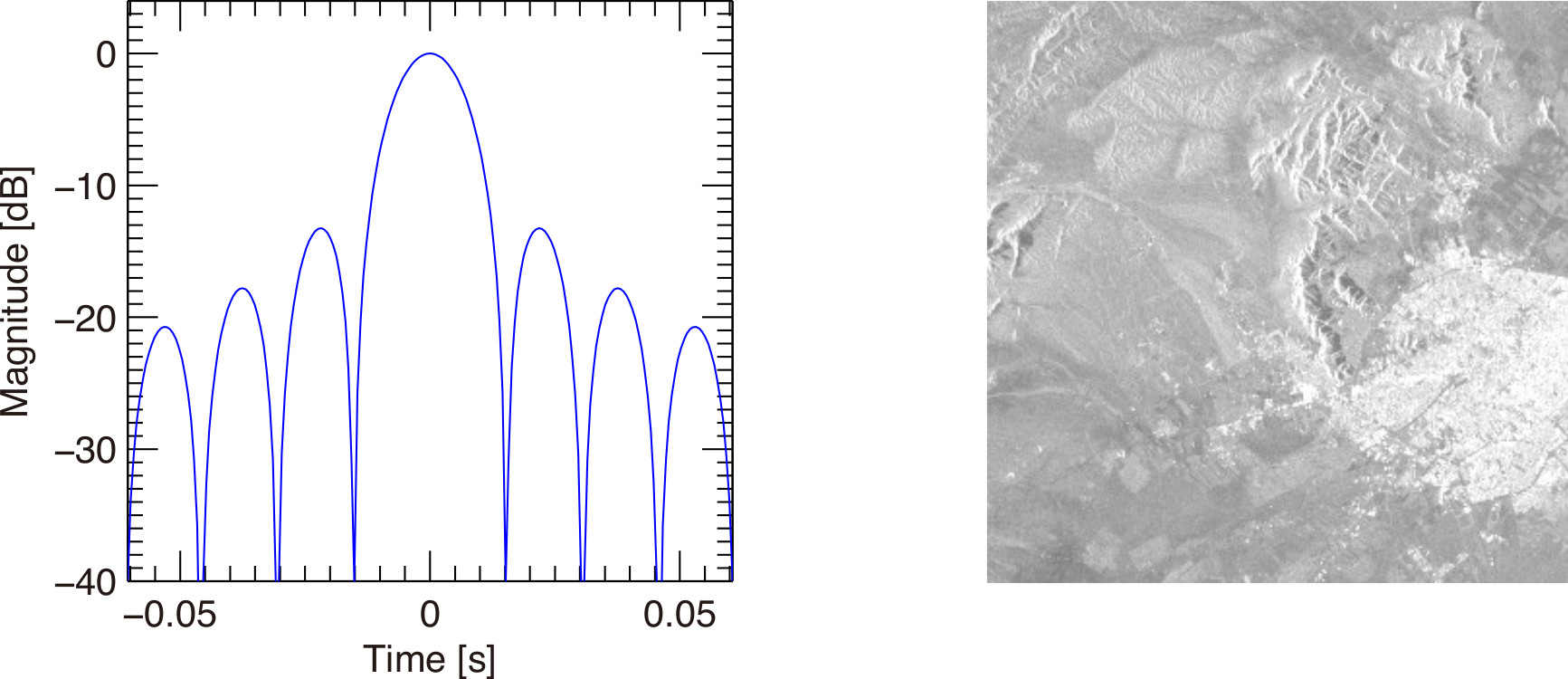

The original data acquired by SAR is called raw data, which is much like pure noise if you view it with an image application. Through signal processing techniques, or focusing, an image can be formed. Further processing, e.g. denoising, is thus performed in the image domain for numerous purposes. Previously one of our group’s focuses is on the processing of data acquired in advanced modes such as spotlight, ScanSAR, TOPS and SweepSAR, which requires more sophisticated signal processing algorithms (e.g. Liang et al., 2017, IEEE TGRS).

Left: point target analysis in focusing. Right: a focused SAR image.

InSAR Algorithms and Software Development, and High Performance Computation

A SAR image is a complex image with both magnitude and phase. By comparing the phases of two radar images, InSAR can measure topography or deformation on the Earth’s surface. The cool thing about satellite InSAR is that it measures deformation on the ground with centimeter or even millimeter precision at an altitude of about 700 km in space. Furthermore, the measurement is an image, which is like deploying millions of GPS stations on the ground to monitor the deformations. By processing many InSAR images with time series analysis techniques, we can further track the temporal evolution of the deformations, which has wide applications.

Synthetic Aperture Radar INterferometry (InSAR)

InSAR is comprised of a number of processing steps, and still has challenges or even bottlenecks. The algorithms are continuously evolving. With ever-growing number of satellite SAR missions and advanced imaging capabilities, the amount of SAR data is exploding - SAR is also entering the big data era. This brings new challenges and opportunities especially for InSAR time series analysis and requires efficient processing techniques. Our group works on developing new algorithms and employing high performance computing techniques such as GPU to tackle the most challenging problems in InSAR (e.g. Liang and Fielding, 2017a, IEEE TGRS, Liang and Fielding, 2017b, IEEE TGRS).

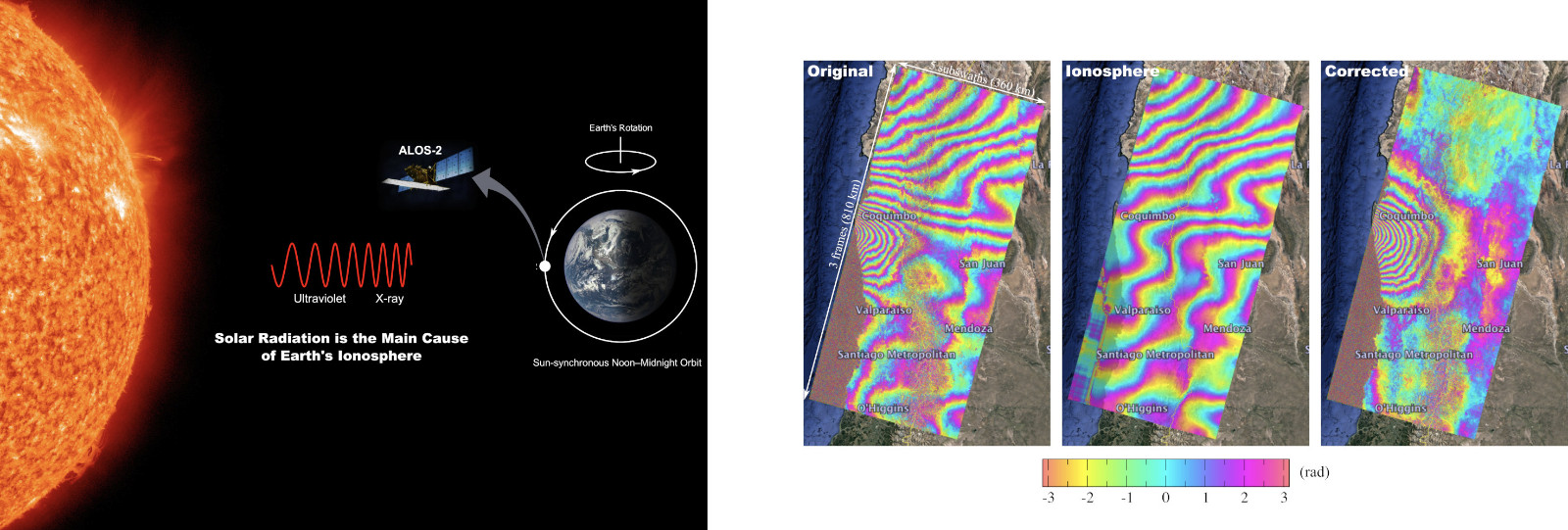

InSAR Error Corrections

While the microwave is travelling in the atmosphere, its phase is mostly affected by two layers of the atmosphere including troposphere and ionosphere. The troposphere is the lowest layer of Earth’s atmosphere. The water vapor in troposphere causes phase delay to microwave signals. The ionosphere can extend from 50 km to 1000 km above the Earth’s surface. Its formation is mainly because the neutral atoms or molecules in the atmosphere eject free electrons after absorbing solar radiation. The free electrons cause a phase shift to the traversing microwave signal. Previously our group has extensively studied the effects of ionosphere and developed a number of techniques to correct its effects.

Left: Ionosphere and satellite synthetic aperture radar. Right: InSAR ionosphere correction result (copyright: Liang Group).

The measured deformation by InSAR contains not only deformation of interest, but also other physical components including the currently known ocean tide and solid earth tide. They mostly introduce very long wavelength signals in the measurement and did not raise wide concern before. However, they are becoming increasingly important as InSAR is moving forward from small-scale deformation measurement to large-scale or even continental-scale measurement thanks to the advanced imaging capabilities of present and future SAR missions.

InSAR processing also introduces errors in the final results. Our group works on the correction of all sources of errors to improve the accuracy and precision of InSAR measurements (e.g. Liang and Fielding, 2017, IEEE TGRS, Liang et al., 2019, IEEE TGRS).

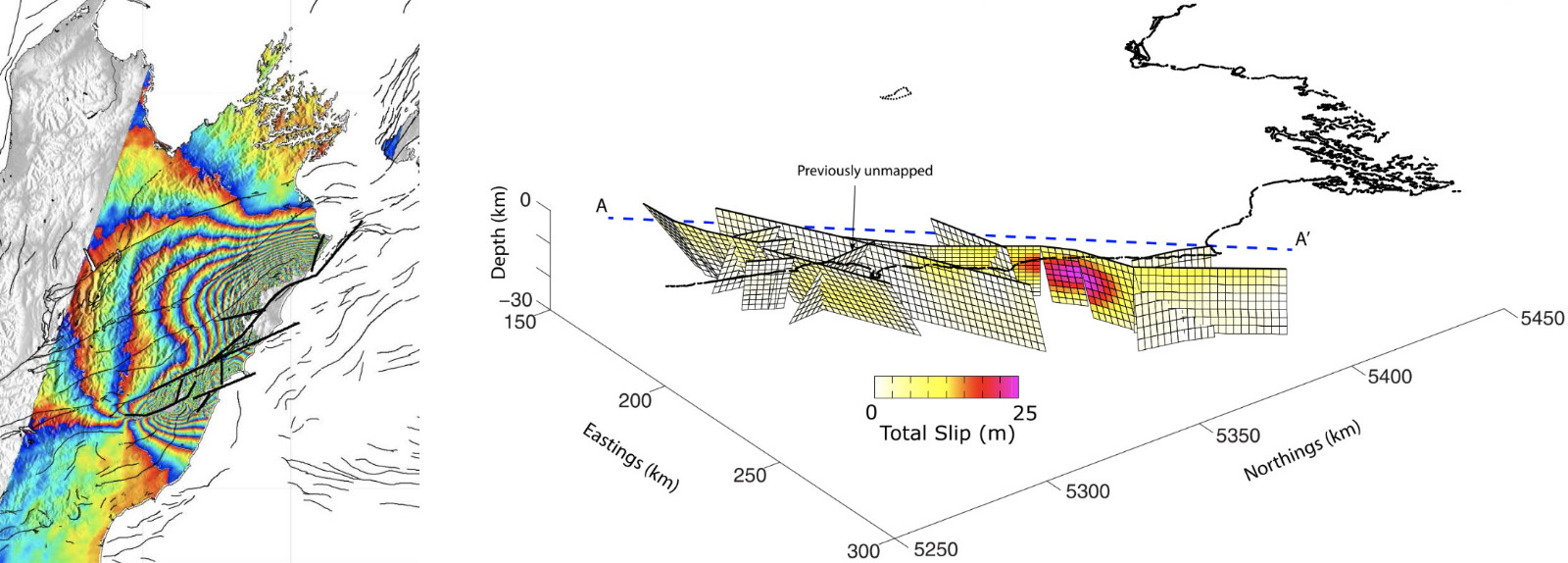

InSAR Applications in Geophysics and other Fields

The unique capabilities of InSAR make it widely used in science and engineering. Researchers have been using InSAR to study earthquakes, tectonics, glaciers, volcanoes, landslide, hydrology etc. InSAR is also used in a number of fields in engineering such as the monitoring of critical infrastructures (e.g. buildings, bridges, dams, tunnels, subways and railways), city subsidence, land subsidence due to oil and water pumping, mining etc. New applications are also emerging in other fields. In some fields, it would have been difficult or even impossible to accomplish without the help of InSAR. Previously our group had collaborated with researchers at major universities such as UC Berkeley, UCLA and Caltech to apply InSAR to the study of significant problems in geophysics (e.g. Hamling et al., 2017, Science).

InSAR data used to study the 2016 Mw 7.8 Kaikōura earthquake in New Zealand. Left: ALOS-2 interferogram. Right: Best-fitting crustal fault model.

Natural Hazard Response with SAR

Radar can image in all weather conditions and without the need of illumination from the Sun. This makes it particularly useful in areas like the cloudy or rainy southern China where geohazards can easily happen. As the number of civil and commercial SAR satellites is growing rapidly, we may be able to detect daily or even hourly surface changes. The results have already been proved to be of great values to government agencies. Previously we have worked with researchers to produce damage proxy maps (DPM) that map the damages caused by various natural disasters. Many of the results have been used to aid in the response of these disasters (e.g. Yun et al., 2015, SRL).

Damage proxy map of the 2015 Nepal earthquake generated using SAR data.